The 8086 Processor

A Brief History

The Intel 8086, released in 1978, marked a pivotal moment in computing history as Intel’s first 16-bit microprocessor. Designed by a team led by Stephen Morse, the 8086 was Intel’s answer to the growing demand for more powerful processors that could handle larger programs and address more memory than the existing 8-bit chips of the era.

The processor introduced the x86 architecture that would become the foundation for decades of computing evolution. With its 16-bit registers and 20-bit address bus 1, the 8086 could access up to 1 megabyte of memory—a massive improvement over the 64KB limitation of 8-bit processors. However, it retained backward compatibility concepts that would prove both beneficial and constraining for future generations.

Why 20-bit Address Bus in the 8086?

The 8086 used a 20-bit address bus, which was a deliberate design decision based on several factors:

Memory Capacity: With 20 address lines, the processor could address 2^20 = 1,048,576 locations, or exactly 1 megabyte of memory. In 1978, this was considered enormous - most computers had only 4KB to 64KB of memory.

Economic Considerations: Adding more address lines would have increased the chip’s pin count, making it more expensive to manufacture and requiring more expensive motherboards. Intel balanced capability with cost-effectiveness.

The Segmented Memory Model

Intel’s previous 8-bit processors contained 8-bit wide registers and 16-bit wide address bus, which can enable addressing of 2^16 = 64KB of memory. So thoeretically a program could use 64KB of memory.

Intel’s main goal was to maintain programming familiarity while expanding addressable memory. They wanted programmers to continue thinking in terms of 16-bit addresses (which they were already comfortable with from 8-bit processors) while secretly accessing a larger memory space. The segmentation model essentially says: “You can still write programs using 16-bit addresses, but we’ll automatically map these into different 64KB ‘segments’ of the larger 1MB space.”

The physical address was divided into 2 parts: selector/segment and offset.

- Selector (Segment): 16-bit value stored in one of CS, DS, ES, SS, etc.

- Offset: 16-bit value (e.g., in SI, DI, BP, SP, or an immediate/displacement).

- Physical Address Calculation: physical_address = (selector × 16) + offset

The idea is to express a 20-bit address using 2 16-bit registers. A selector register (CS, DS, ES, SS) indicates the starting address of the segment and the offset register (SI, DI, BP, SP) indicates the boundary of the segment. Since the offset is 16-bits, the boundary can be at a maximum of 64KB thus maintaining backward compatibility.

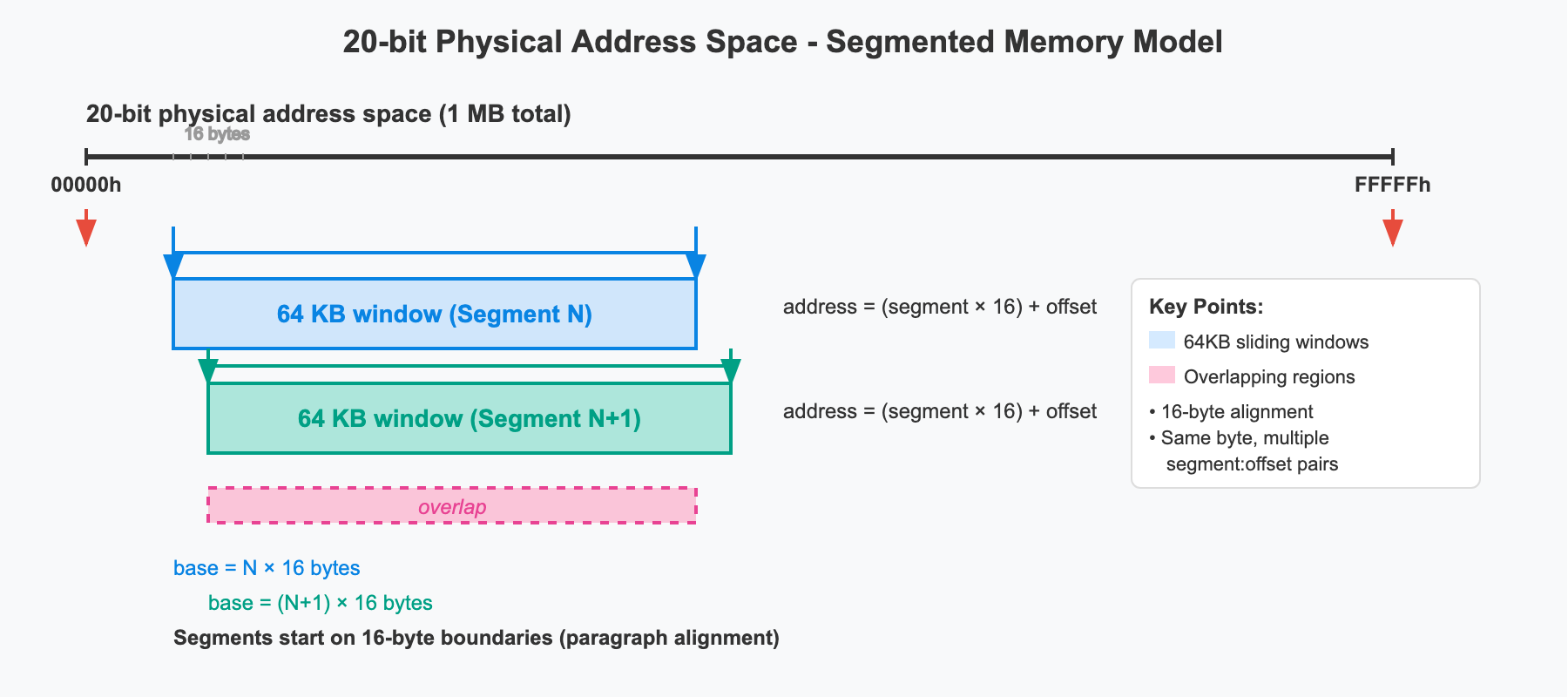

What the diagram shows

A segment is not a fixed block—it’s a sliding 64 KB window that can start on any 16-byte paragraph.

Segment value = paragraph number; multiplying by 16 shifts the window left or right in 16-byte steps.Segment N and Segment N+1 start only 16 bytes apart, so their two 64 KB windows overlap almost completely.

Any physical byte inside that overlap can be reached with two (or many more) different segment:offset pairs.Because the window can slide to 65,536 different paragraph positions (0000h–FFFFh), the segment register must be 16 bits wide—not just 4 bits.

The offset (0–65535) always selects the byte inside the current 64 KB window.

Together, segment and offset build the 20-bit physical address:

Disadvantages of the Segmentation Model

64 KB Segment Limit:

- Each selector covers only 64 KB (the 16-bit offset range). Although it was theoretically possible to support a higher offset which means larger segment memory for a program.

- Large programs or data structures must be split across multiple segments.

- Switching segments (e.g., changing CS or DS) adds overhead and complexity.

Alias Addresses:

- The same physical byte can be addressed by many segment:offset pairs.

- Example: physical 04808₁₆ = 047C:0048 = 047D:0038 = 047E:0028 = 047B:0058

- Makes comparing or normalizing pointers tricky.

Wrap Around after 20 bits:

- All segments after 0xF000 reference memory positions above the 1 MB address space that don’t exist, which the 8086 chose to wrap around by ignoring the 21st bit of an address. After all, there is no 21st line in the address bus.

The Real Mode

Real mode is the operating mode that all x86 processors boot into, providing direct hardware access and backward compatibility with the original 8086 processor. Named “real” because it provides direct, unsupervised access to real physical memory addresses without any protection mechanisms or virtual memory translation.

When an x86 processor powers on, it starts in real mode regardless of whether it’s a modern 64-bit CPU or the original 8086. This ensures that decades-old software can still run and that the boot process remains consistent across the entire x86 family.

Contents of 1MB memory layout in 8086 real mode

FFFFFh ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ System ROM BIOS (64KB) │

│ • Boot code and POST routines │

│ • Hardware initialization │

│ • Interrupt handlers (INT 10h, 13h, 16h, etc.) │

│ • System services and utilities │

F0000h ├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Expansion ROM Area (192KB) │

│ • Network card ROM │

│ • SCSI controller ROM │

│ • Other adapter ROM │

│ • Often partially unused │

C0000h ├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Video BIOS ROM (128KB) │

│ • VGA/EGA BIOS routines │

│ • Graphics mode setup │

│ • Character font data │

│ • Display adapter firmware │

A0000h ├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Video RAM (128KB) │

│ A0000h-AFFFFh: EGA/VGA graphics memory (64KB) │

│ B0000h-B7FFFh: Monochrome text memory (32KB) │

│ B8000h-BFFFFh: Color text memory (32KB) │

90000h ├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Extended Conventional Memory (576KB) │

│ • Available for programs if installed │

│ • Many early systems had less RAM │

│ • Could be used for disk buffers, RAM disks │

│ • Upper portion often used by DOS itself │

A0000h ├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤ ← 640KB barrier

│ │

│ Conventional Memory (640KB) │

│ Main user program area │

│ │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ User Program Area │ │

│ │ • Application programs │ │

│ │ • Program data and variables │ │

│ │ • Dynamic memory allocation │ │

│ │ • TSR (Terminate and Stay Resident) programs │ │

│ └─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ DOS Kernel and System Files │ │

│ │ • COMMAND.COM │ │

│ │ • Device drivers │ │

│ │ • File allocation tables │ │

│ │ • Directory buffers │ │

│ └─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

00500h ├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ BIOS Data Area (256 bytes) │

│ • Hardware configuration data │

│ • Equipment list │

│ • Keyboard buffer │

│ • Video mode information │

│ • Serial/parallel port addresses │

│ • Timer tick count │

│ • Memory size information │

003FFh ├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Interrupt Vector Table (1024 bytes) │

│ • 256 interrupt vectors × 4 bytes each │

│ • Each vector: segment:offset (2 bytes:2 bytes) │

│ • INT 00h-FFh handler addresses │

│ • Hardware and software interrupts │

│ • Critical for system operation │

00000h └─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Key Memory Regions

- Interrupt Vector Table (00000h-003FFh)

- Size: 1024 bytes (256 vectors × 4 bytes each)

- Structure: Each entry contains segment:offset pointer (YYYY:XXXX format)

- Purpose: The system’s “phone book” for interrupt handlers

- Function: When hardware or software triggers an interrupt (like pressing a key), the CPU looks up the handler address here

- Critical vectors:

- INT 08h: System timer (18.2 times per second)

- INT 09h: Keyboard interrupt

- INT 10h: Video services

- INT 13h: Disk services

- INT 16h: Keyboard services

- INT 21h: DOS system calls

- Why it’s at address 0: The CPU automatically multiplies the interrupt number by 4 to find the handler address, so INT 09h handler is at 0×4×9 = 36 (0024h).

- BIOS Data Area (00400h-004FFh) - 256 bytes

- Purpose: System configuration and status information

- Hardware ports: COM1-4 2 and LPT1-3 3 base addresses

- Video info: Current video mode, screen dimensions, cursor position

- Keyboard: Shift/Ctrl/Alt key states 4, keyboard buffer 5

- System info: Installed memory size, equipment flags

- Timers: System tick count since boot

- Conventional Memory (00500h-9FFFFh) - ~640KB

- Purpose: Main workspace for operating system and applications

- DOS Kernel Area (lower portion)

- COMMAND.COM: The DOS command interpreter

- DOS kernel: File system, memory management, process control

- Device drivers: Disk drivers, printer drivers, etc.

- System buffers: File allocation table cache, directory buffers

- User Program Area (upper portion)

- Application programs: Your actual software

- Program data: Variables, arrays, user data

- Dynamic allocation: Heap memory for runtime allocation

- TSR programs: Background utilities (like antivirus, print spoolers)

- Why 640KB limit: IBM reserved the upper 384KB for hardware, creating the famous “640KB ought to be enough” barrier.

Video RAM (A0000h-BFFFFh) - 128KB

- Purpose: Direct access to display memory

- A0000h-AFFFFh: Graphics Memory (64KB)

- EGA/VGA framebuffer: Each byte represents pixel data

- Direct pixel control: Writing here immediately changes screen pixels

- Mode-dependent: Layout changes based on resolution and color depth

B0000h-B7FFFh: Monochrome Text (32KB)

- Character display: For monochrome monitors

- Text mode: 80×25 characters, 2 bytes per character (char + attribute)

B8000h-BFFFFh: Color Text (32KB)

- Color character display: Standard color text mode

- Format: Byte pairs (character, attribute)

- Example: Writing ‘A’ (65) + 0x07 (white on black) to B8000h displays ‘A’ at top-left

Video BIOS ROM (C0000h-C7FFFh) - 32KB

- Purpose: Graphics card firmware and services

- Font data: Character sets for text modes

- Hardware control: Register programming for graphics chips

- BIOS extensions: Additional video services beyond basic BIOS

- Memory-mapped: This is ROM on the graphics card, not system RAM.

Expansion ROM Area (C8000h-EFFFFh) - 160KB

- Purpose: Additional adapter card firmware

- Network cards: Boot ROM for network booting

- SCSI controllers: Disk controller firmware

- Sound cards: Audio processing firmware

- Other adapters: Any card that needs ROM space

- Often unused: Many systems had empty areas here.

System ROM BIOS (F0000h-FFFFFh) - 64KB

- Purpose: Core system firmware

- Power-On Self Test (POST): Hardware diagnostics at boot

- Bootstrap loader: Loads operating system from disk

- Hardware drivers: Low-level hardware access routines

- System services: INT 10h (video), INT 13h (disk), INT 16h (keyboard)

- Reset vector: CPU starts execution at FFFF:0000 on power-up

Why This Layout?

- Hardware Requirements: Different devices need different address ranges

- ROM needs upper memory: BIOS must be at top (reset vector at FFFFFh)

- Video needs fast access: Memory-mapped for performance

- Programs need contiguous space: Large conventional memory block

The 80286 and protected mode

Introduction to the 80286

The Intel 80286, released in 1982, represented a revolutionary leap in x86 architecture. While maintaining backward compatibility with the 8086, it introduced protected mode - a sophisticated operating environment that broke free from real mode’s limitations and laid the foundation for modern computing.

The 80286 was Intel’s answer to the growing demands for multitasking operating systems, memory protection, and the ability to address more than 1MB of memory. It powered the IBM PC/AT and became the processor that truly enabled the transition from simple DOS machines to powerful workstations.

Key Innovations of the 80286

16MB Address Space

- 24-bit address bus (compared to 8086’s 20-bit)

- 16MB maximum memory (2^24 = 16,777,216 bytes)

- Maintained real mode compatibility for existing

Hardware Memory Protection

- Privilege levels preventing user programs from corrupting system memory

- Segment-level protection with access rights and bounds checking

- Hardware-enforced security that software cannot bypass

Virtual Memory Foundation

- Segment descriptors containing detailed memory management information

- Global and Local Descriptor Tables for memory organization

- Task switching support enabling true multitasking

Addressing 24-Bit Memory

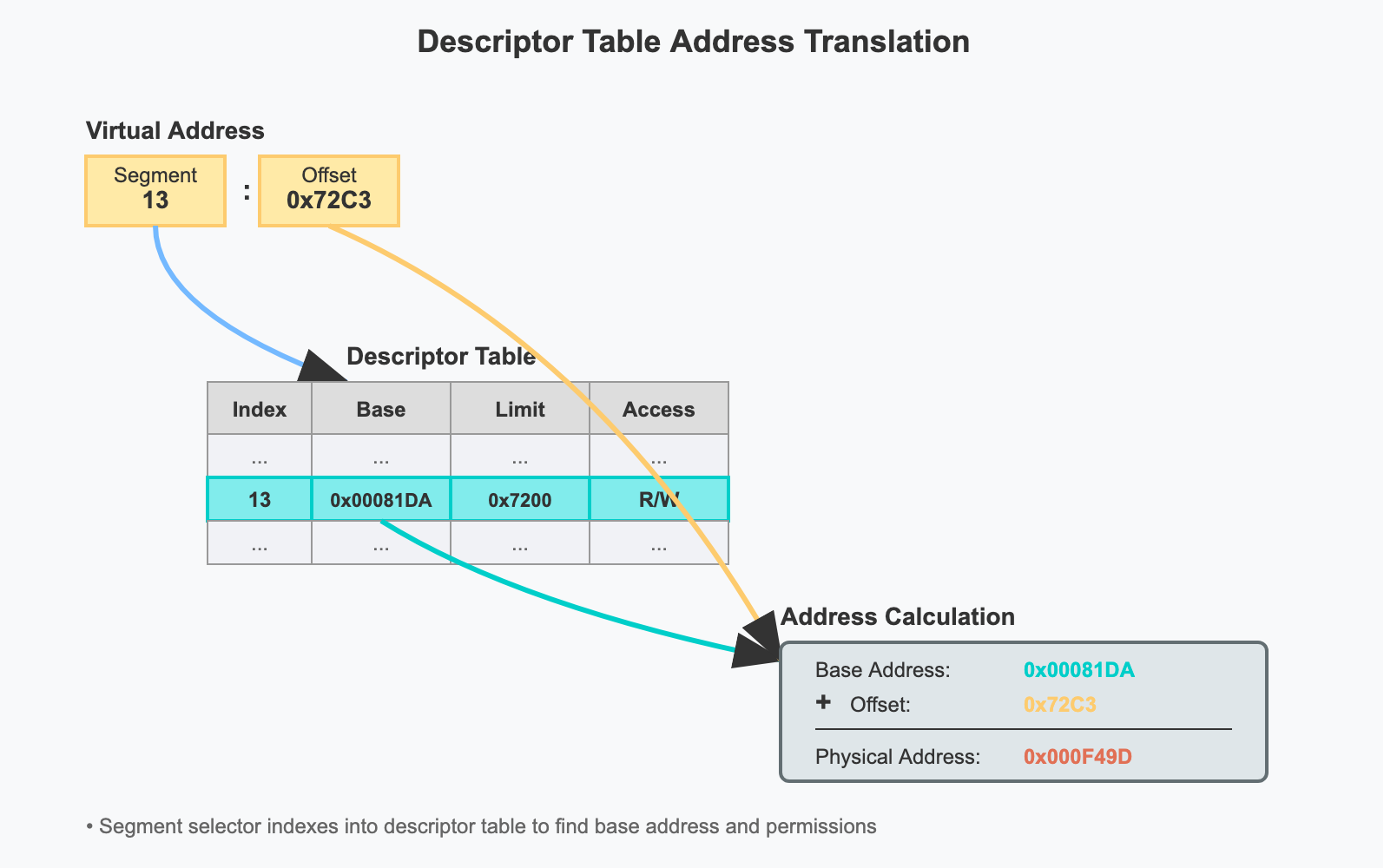

The 80286 processor had 24 address bus compared to 20-Bit address bus of 8086. It had to implement the addressing in such a way that its backward compatible with 8086 processor’s addressing. Instead of extending the logic used in 8086’s real mode addressing, 80286 took an entirely different approach. The memory was still addressed with selector (16-Bit): offset (16-Bit) pairs. In real mode, a selector value was a paragraph number of physical memory. In protected mode, a selector value is an index into a descriptor table. In both modes, programs are divided into segments. In real mode, these segments are at fixed positions in physical memory and the selector value denotes the paragraph number of the beginning of the segment.

While we are storing the actual physical address of the segment in descriptor table, the descriptor table entry can store other information related to the segment as well. For eg: length of the segment which can be used to check if the memory accessed by the program is within the segment, read/write flags which can be used to enforce protection, etc.

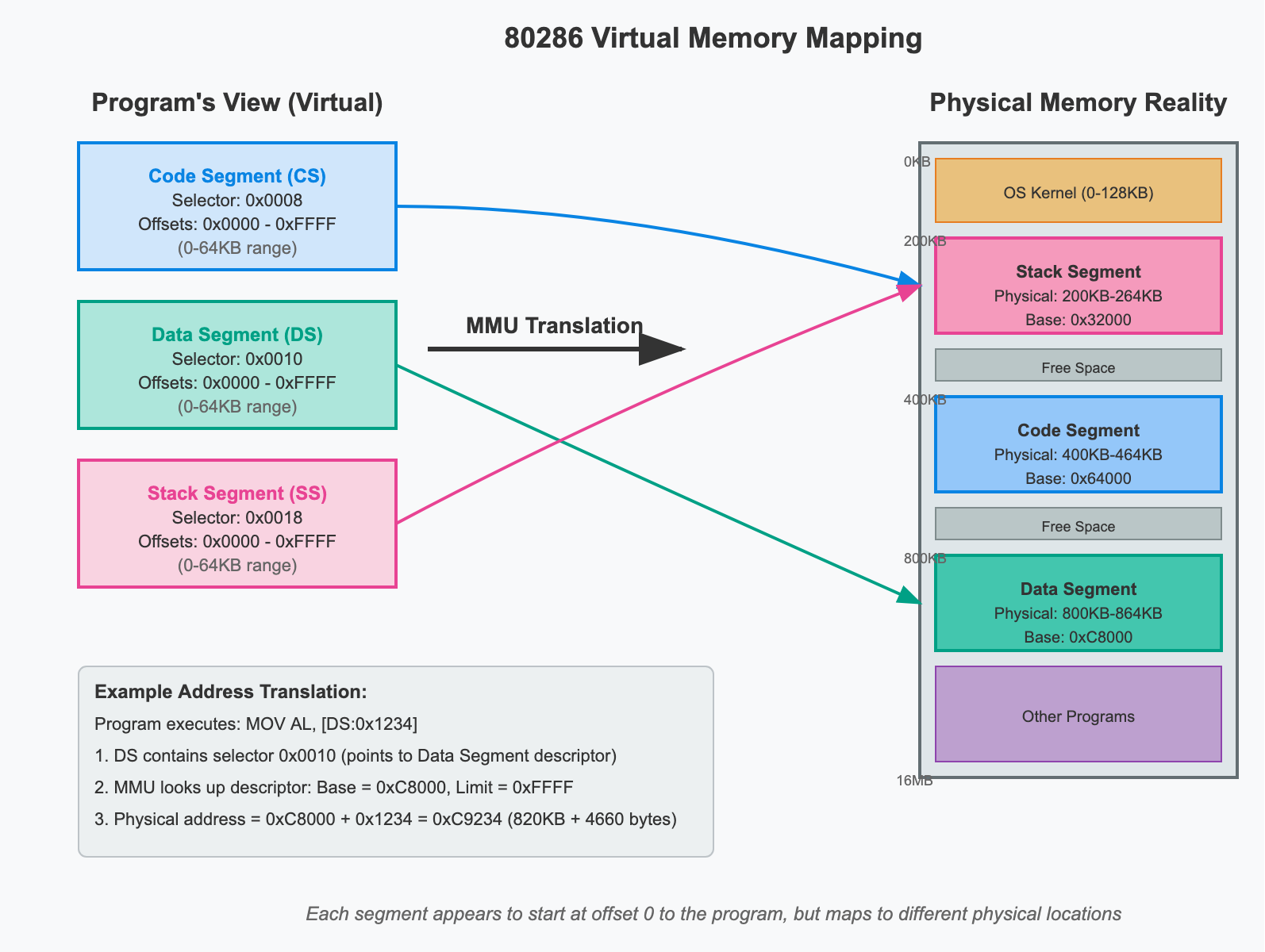

The Virtual Memory

The idea of virtual memory is provide an illusion to a program that it is the only program running and it has access to all the memory. The 80286 introduced the foundational concepts of virtual memory to the x86 architecture, though it implemented a more limited form compared to modern processors. Understanding the 80286’s approach helps clarify why virtual memory became essential and how it evolved.

Virtual memory creates an abstraction layer between what programs think they’re accessing (virtual addresses) and what actually exists in physical memory. The 80286 achieved this through segmentation-based virtual memory.

Simplified Programming Model with Virtual Memory

Before virtual memory, programmer had to directly manage physical addresses which is error prone and there’s a possibility of overwriting other program’s data. This also means the programmer has to know where the segments will be loaded in memory beforehand. Virtual Memory solves this issue as each segment will be under the illusion that it starts at memory address 0 and can access upto 64KB of memory.

Global and Local Descriptor Tables (GDT and LDT)

What Are Descriptor Tables?

Think of descriptor tables as address books for the computer’s memory system. Just like you use a phone book to look up someone’s address when you only know their name, the 80286 processor uses descriptor tables to look up memory information when it only knows a selector (a kind of memory “name”).

The Basic Problem They Solve

In real mode, programs had to deal with physical memory addresses directly:

Real Mode Problem:

Program says: "I want to access memory at 0x12345"

CPU responds: "OK, accessing physical memory at 0x12345"

Issues:

- Programs must know exact physical addresses

- No protection between programs

- Programs can corrupt each other's memory

- Hard to relocate programs in memory

Protected mode solves this with an indirection layer:

Protected Mode Solution:

Program says: "I want to access selector 0x0008, offset 0x1234"

CPU responds: "Let me look up selector 0x0008 in the descriptor table..."

CPU finds: "Selector 0x0008 points to base address 0x100000"

CPU calculates: "Physical address = 0x100000 + 0x1234 = 0x101234"

CPU verifies: "Access allowed? Yes. Accessing physical memory at 0x101234"

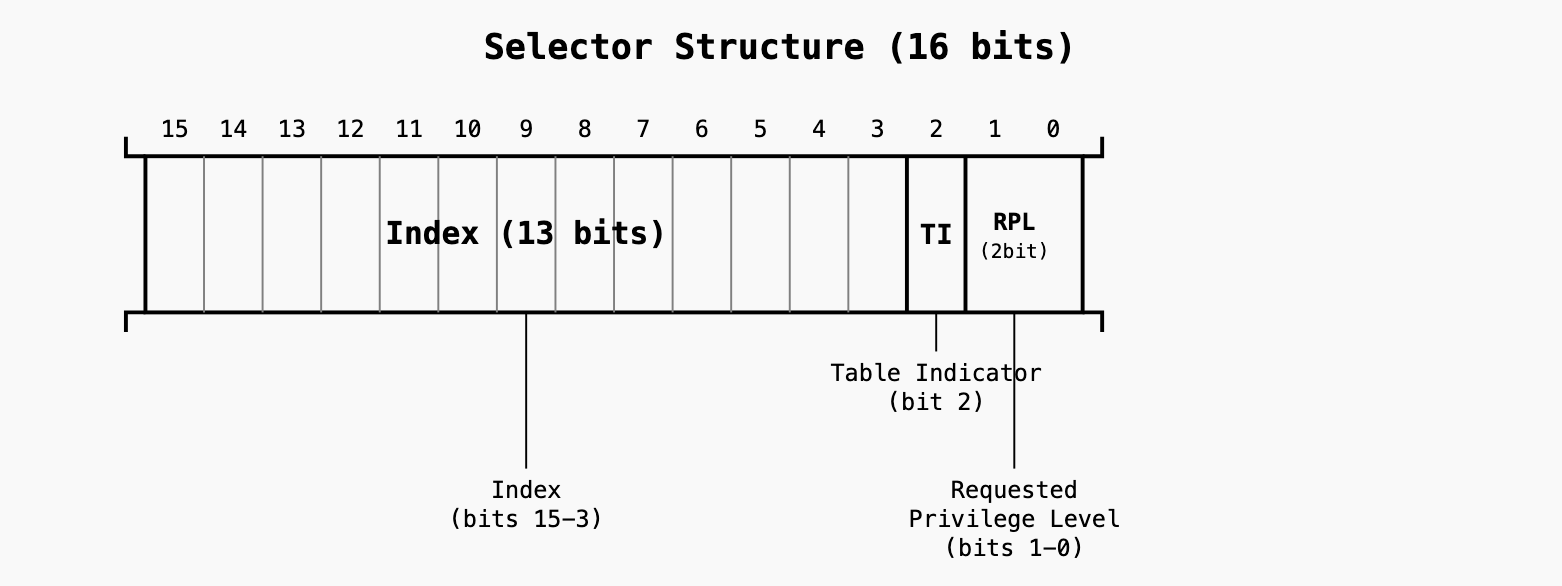

Understanding Selectors

A selector is a 16-bit value that acts like a “memory ID card.” Instead of using physical addresses, programs use selectors to identify memory segments.

- Index (bits 15-3): Which entry in the descriptor table (0-8191)

- TI (bit 2): Table Indicator - 0 = GDT, 1 = LDT

- RPL (bits 1-0): Requested Privilege Level (0-3)

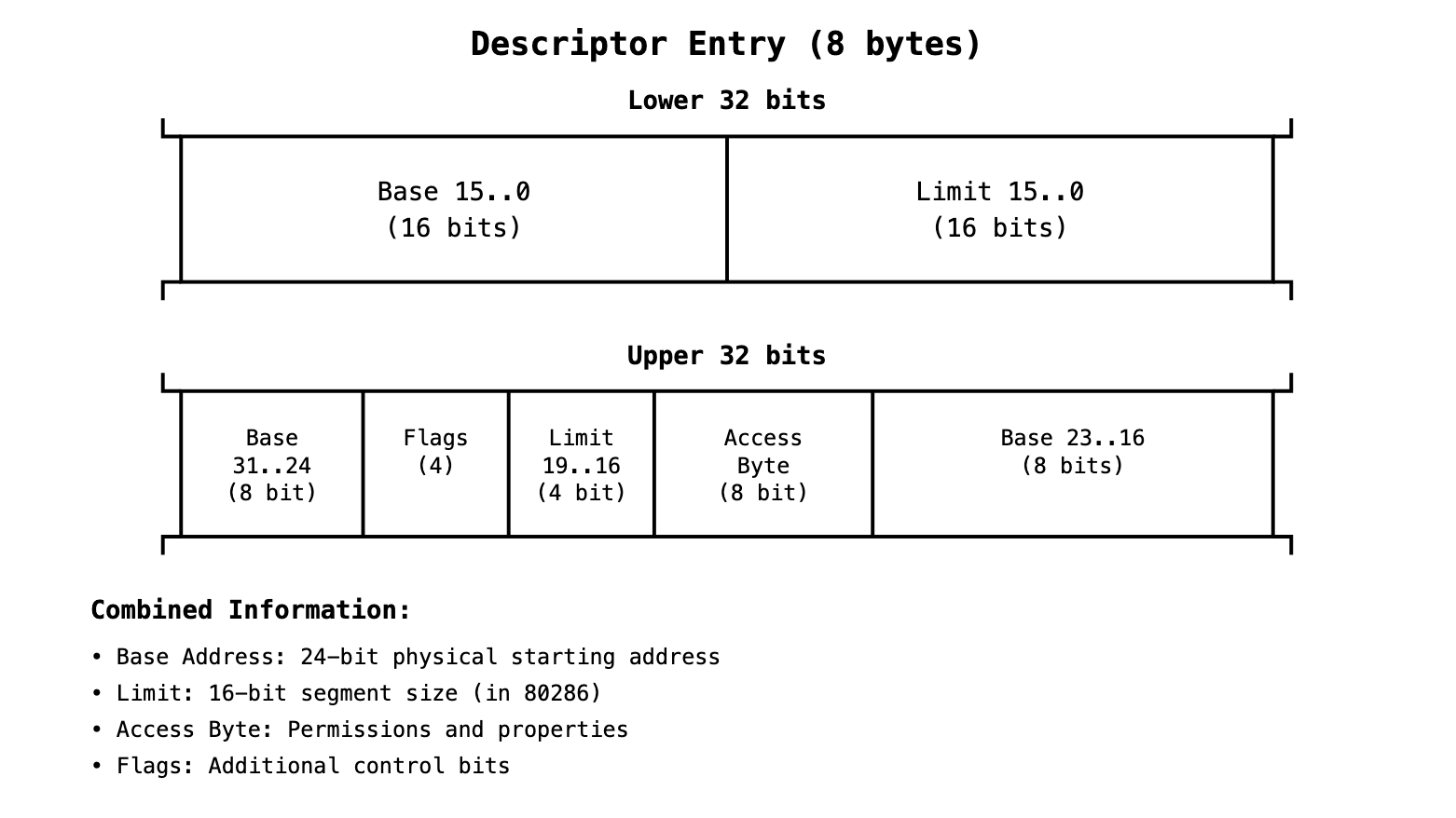

What Is a Descriptor?

A descriptor is an 8-byte data structure that contains all the information the CPU needs to access a memory segment safely.

Base Address (24 bits total in 80286): (Base[23..16] + Base[15..0])

- Bits 15..0 from the lower section

- Bits 23..16 from the upper section

Limit (20 bits total, but 80286 only uses 16 bits):

- Limit 15..0 (16 bits) - from Lower 32 bits

- Limit 19..16 (4 bits) - from Upper 32 bits (but not used in 80286)

The descriptor format was designed to be forward-compatible. The 80386 later extended it to use:

- Full 32-bit base address (adding Base 31..24)

- Full 20-bit limit (adding Limit 19..16 with granularity bit)

Final physical address calculation:

Physical Address = 24-bit Base (from descriptor) + 16-bit Offset (from instruction)

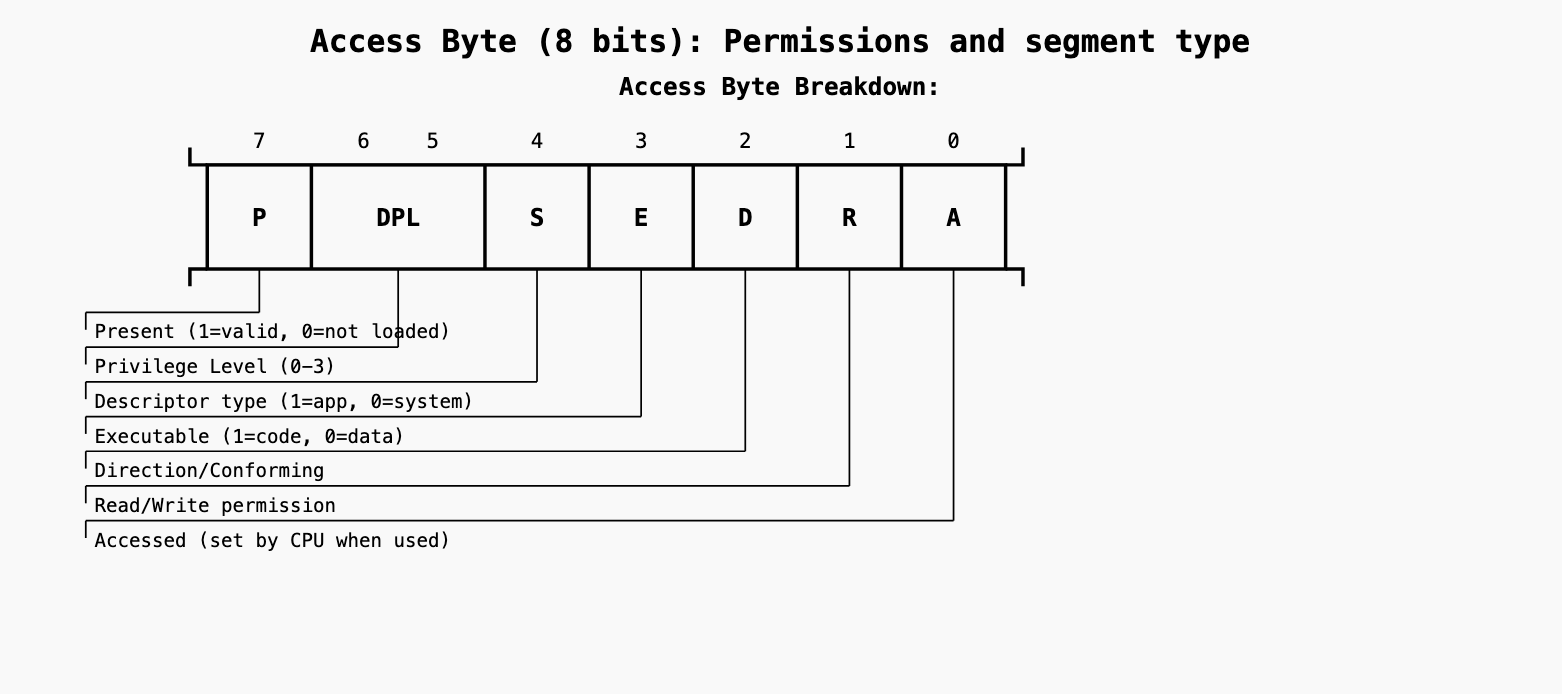

Access Byte Format

- P (Present) - Bit 7: Indicates whether the segment is currently loaded in memory. When P=1, the segment is valid and can be accessed. When P=0, any attempt to access this segment generates a segment-not-present exception, allowing the OS to load the segment from disk (virtual memory support).

- DPL (Descriptor Privilege Level) - Bits 6-5: Defines the privilege level required to access this segment (0-3, where 0 is most privileged). Code running at privilege level 3 (user mode) cannot access segments with DPL=0 (kernel mode). This enforces memory protection between kernel and user space.

- S (System) - Bit 4: Distinguishes between application segments and system segments. When S=1, this is an application segment (code/data used by programs). When S=0, this is a system segment (like Task State Segment or LDT descriptor) used by the processor for special operations.

- E (Executable) - Bit 3: Determines if this segment contains executable code or data. When E=1, this is a code segment that can be executed (instructions fetched from here). When E=0, this is a data segment used for storing variables and cannot be executed.

- D (Direction/Conforming) - Bit 2: For data segments: D=0 means segment grows upward (normal), D=1 means grows downward (stack). For code segments: D=0 means non-conforming (strict privilege checking), D=1 means conforming (can be called from lower privilege levels without changing CPL).

- R (Read/Write) - Bit 1: For data segments: R=1 allows write access, R=0 makes it read-only. For code segments: R=1 allows reading the code (useful for debuggers), R=0 makes it execute-only. Code segments are never writable regardless of this bit.

- A (Accessed) - Bit 0: Automatically set by the CPU whenever the segment is accessed (loaded into a segment register or used). Never cleared by hardware - only software can clear it. Used by operating systems to implement virtual memory algorithms by tracking which segments are actively being used.

Flags Field (4 bits)

Bit 3: G (Granularity)

G = 0: Limit is in bytes (fine granularity)

- Segment can be 1 byte to 1 MB in size

- Limit value is used directly

G = 1: Limit is in 4KB pages (page granularity)

- Segment can be 4KB to 4GB in size

- CPU automatically shifts limit left by 12 bits (multiplies by 4096)

Bit 2: D/B (Default/Big)

For Code Segments: Controls default operand/address size

- D = 0: 16-bit mode (8086/80286 compatible)

- D = 1: 32-bit mode (80386+ native)

For Data Segments: Controls stack pointer size

- B = 0: Stack uses SP (16-bit stack pointer)

- B = 1: Stack uses ESP (32-bit stack pointer)

Bit 1: L (Long Mode)

- For 64-bit mode only (not relevant for 80286)

- L = 0: Not a 64-bit code segment

- L = 1: 64-bit code segment (x86-64 mode)

- Rule: If L = 1, then D must = 0

Bit 0: AVL (Available)

- Available for system software use

- Not used by CPU hardware

- OS can use for its own purposes

- Examples: Process tracking, debugging flags, memory management hints

Global Descriptor Table (GDT)

The Global Descriptor Table is a system-wide table containing descriptors that all tasks can potentially access. Think of it as the “public directory” of memory segments.

GDT Structure and Location

Physical Memory Layout:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ System RAM │

│ │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ GDT │ │

│ ├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤ │

│ │ Entry 0: NULL Descriptor (required) │ │

│ ├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤ │

│ │ Entry 1: Kernel Code Segment │ │

│ ├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤ │

│ │ Entry 2: Kernel Data Segment │ │

│ ├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤ │

│ │ Entry 3: User Code Segment │ │

│ ├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤ │

│ │ Entry 4: User Data Segment │ │

│ ├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤ │

│ │ Entry 5: Task A's LDT Descriptor │ │

│ ├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤ │

│ │ Entry 6: Task A's TSS Descriptor │ │

│ ├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤ │

│ │ Entry 7: Task B's LDT Descriptor │ │

│ ├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤ │

│ │ Entry 8: Task B's TSS Descriptor │ │

│ └─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

GDTR Register (inside CPU):

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Base Address: Points to start of GDT in memory │

│ Limit: Size of GDT - 1 │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

What Goes in the GDT?

System-wide resources that multiple tasks might need:

1. Operating System Segments

- Kernel code segment (Ring 0)

- Kernel data segment (Ring 0)

- System service segments

2. Common User Segments

- Standard user code segment (Ring 3)

- Standard user data segment (Ring 3)

3. Task Management Descriptors

- Task State Segments (TSS) for each task

- Local Descriptor Table (LDT) descriptors for each task

4. Device Driver Segments

- Driver code segments

- Shared system libraries

Example GDT Layout

┌─────┬───────────────────┬──────────┬─────────┬─────────────────┐

│Index│ Description │ Base │ Limit │ Access Rights │

├─────┼───────────────────┼──────────┼─────────┼─────────────────┤

│ 0 │ NULL (required) │ 00000000 │ 00000 │ 00000000 │

├─────┼───────────────────┼──────────┼─────────┼─────────────────┤

│ 1 │ Kernel Code │ 00000000 │ FFFFF │ 9A (Ring 0, X/R)│

├─────┼───────────────────┼──────────┼─────────┼─────────────────┤

│ 2 │ Kernel Data │ 00000000 │ FFFFF │ 92 (Ring 0, R/W)│

├─────┼───────────────────┼──────────┼─────────┼─────────────────┤

│ 3 │ User Code │ 00000000 │ FFFFF │ FA (Ring 3, X/R)│

├─────┼───────────────────┼──────────┼─────────┼─────────────────┤

│ 4 │ User Data │ 00000000 │ FFFFF │ F2 (Ring 3, R/W)│

├─────┼───────────────────┼──────────┼─────────┼─────────────────┤

│ 5 │ Text Editor LDT │ 00200000 │ 01000 │ 82 (LDT, Ring 0)│

├─────┼───────────────────┼──────────┼─────────┼─────────────────┤

│ 6 │ Text Editor TSS │ 00201000 │ 00068 │ 89 (TSS, Ring 0)│

├─────┼───────────────────┼──────────┼─────────┼─────────────────┤

│ 7 │ Web Browser LDT │ 00300000 │ 01000 │ 82 (LDT, Ring 0)│

├─────┼───────────────────┼──────────┼─────────┼─────────────────┤

│ 8 │ Web Browser TSS │ 00301000 │ 00068 │ 89 (TSS, Ring 0)│

└─────┴───────────────────┴──────────┴─────────┴─────────────────┘

Local Descriptor Table (LDT)

A Local Descriptor Table is a task-specific table containing descriptors that are private to one particular task. Think of it as each task’s “private address book.”

Key Differences: GDT vs LDT

GDT (Global - Shared): LDT (Local - Private):

┌─────────────────────┐ ┌─────────────────────┐

│ • One per system │ │ • One per task │

│ • Shared by all │ │ • Private to task │

│ • System resources │ │ • Task resources │

│ • Always available │ │ • Only when task │

│ │ │ is running │

└─────────────────────┘ └─────────────────────┘

How LDTs Work

Step 1: LDT Descriptor in GDT The GDT contains a descriptor that points to each task’s LDT:

GDT Entry 5 (Text Editor's LDT):

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Base: 0x200000 ← Physical address where LDT is stored │

│ Limit: 0x1000 ← LDT can hold up to 512 descriptors │

│ Type: LDT ← This is an LDT descriptor │

│ DPL: 0 ← Ring 0 (system manages LDTs) │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Step 2: LDT Contains Task’s Private Descriptors

At physical address 0x200000 (Text Editor's LDT):

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Entry 0: NULL │

│ Entry 1: Text Editor Code Segment │

│ Entry 2: Text Editor Data Segment │

│ Entry 3: Text Editor Stack Segment │

│ Entry 4: Document Buffer Segment │

│ Entry 5: Font Library Segment │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

LDT Entries

LDT entries follow the exact same 8-byte descriptor format as GDT entries. An LDT is a block of (linear) memory up to 64K in size, just like the GDT. The difference from the GDT is in the Descriptors that it can store, and the method used to access it.

Both use the same:

- 64-bit (8-byte) descriptor structure

- Same Base/Limit/Access byte/Flags layout

- Same bit positions for all fields

However, there are content restrictions for LDT:

- LDT cannot hold system segments (Task State Segments and Local Descriptor Tables)

- LDT can only contain application segments (code/data) and some gates

- GDT can contain everything (application segments, system segments, LDT descriptors, TSS descriptors)

What Are Gates?

Gates are special descriptors that act as “doorways” for controlled transfers of execution. Unlike regular segment descriptors that point to memory regions, gates contain entry points (addresses) where execution should transfer to.

Types of Gates in x86:

1. Call Gates

- Purpose: Allow controlled calls from lower privilege code to higher privilege code

- Function: Like a “secure function pointer” - lets user code (Ring 3) safely call kernel functions (Ring 0)

- Contains: Target code segment selector + offset where to jump

- Security: CPU automatically checks privilege levels and switches stacks if needed

2. Task Gates

- Purpose: Trigger hardware task switches

- Function: Points to a TSS descriptor to switch to a different task

- Contains: TSS selector that identifies which task to switch to

- Usage: Can be placed in IDT for task-switching interrupts

3. Interrupt Gates

- Purpose: Handle interrupts and exceptions

- Function: Similar to call gates but for interrupt handling

- Contains: Target code segment + interrupt handler address

- Behavior: Automatically disables interrupts when called

4. Trap Gates

- Purpose: Handle exceptions and software interrupts

- Function: Like interrupt gates but doesn’t disable interrupts

- Contains: Target code segment + exception handler address

- Usage: For system calls and debugging exceptions

Why Gates Can Be in LDT:

While LDT cannot contain system segments (TSS, LDT descriptors), it can contain gates because:

- Call gates: Allow process-specific entry points to system services

- Task gates: Could theoretically allow process-specific task switching (though rarely used)

Example Use Case:

Process A's LDT might contain:

├── Code Segment (Ring 3)

├── Data Segment (Ring 3)

├── Call Gate → Kernel function for file I/O

└── Call Gate → Kernel function for memory allocation

This way, each process can have its own set of “approved” kernel entry points through call gates in their private LDT, while the kernel maintains control over exactly which functions can be called and how.

In practice: Modern operating systems rarely use LDTs or gates, preferring software-based system call mechanisms and paging-based memory protection. But the hardware still supports these features for compatibility and specialized use cases.

GDTR and LDTR

The processor locates the GDT and the current LDT in memory by means of the GDTR and LDTR registers. These registers store the base addresses of the tables in the linear address space and store the segment limits.

GDTR (Global Descriptor Table Register):

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ GDTR - Simple pointer structure │

├─────────────────────────────────┬───────────────────────────┤

│ Base Address (32-bit) │ Limit (16-bit) │

│ Linear address of GDT in memory │ Size of GDT - 1 │

└─────────────────────────────────┴───────────────────────────┘

- Direct pointer to GDT location in memory

- Loaded with

LGDTinstruction - Contains actual memory address and size

LDTR (Local Descriptor Table Register):

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ LDTR - Segment register with selector + cached descriptor │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Visible: LDT Selector (16-bit) │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Hidden: Cached LDT Descriptor (64-bit) │

│ Base + Limit + Access Rights from GDT entry │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

- Indirect reference through GDT selector

- The LDT is defined as a ’normal’ memory Segment inside the GDT - simply with a Base memory address and Limit

- Loaded with LLDT instruction using a selector

- CPU automatically fetches LDT descriptor from GDT and caches it

The Relationship:

- GDTR points directly to GDT in memory

- LDTR contains a selector that points to an entry within the GDT

- That GDT entry describes where the LDT is located

- CPU caches that LDT descriptor information from GDT in LDTR’s hidden part

WHo can Read/Write into GDTR and LDTR registers?

GDTR (Global Descriptor Table Register):

- Set by: Operating system kernel (Ring 0 code only)

- Instructions: LGDT (Load GDT) and SGDT (Store GDT)

- Privilege: These instructions can only be executed in Ring 0 (kernel mode)

- When: During OS boot/initialization

LDTR (Local Descriptor Table Register):

- Set by: Operating system kernel (Ring 0 code only)

- Instructions: LLDT (Load LDT) and SLDT (Store LDT)

- Privilege: Ring 0 only

- When: During task/process creation or context switches

Initial Setup Process:

1. System Boot Sequence:

1. CPU starts in Real Mode (no GDTR/LDTR)

2. Bootloader loads OS kernel

3. Kernel creates initial GDT in memory

4. Kernel executes LGDT to set GDTR

5. Kernel switches to Protected Mode

6. Kernel can now create LDTs and set LDTR as needed

2. GDT Creation (by OS Kernel):

// Kernel code (Ring 0) during boot

struct gdt_entry gdt[8]; // Array in kernel memory

// Set up null descriptor (entry 0)

gdt[0] = {0};

// Set up kernel code segment (entry 1)

gdt[1] = {base: 0, limit: 0xFFFFF, access: 0x9A, flags: 0xC};

// Set up kernel data segment (entry 2)

gdt[2] = {base: 0, limit: 0xFFFFF, access: 0x92, flags: 0xC};

// Set up user code segment (entry 3)

gdt[3] = {base: 0, limit: 0xFFFFF, access: 0xFA, flags: 0xC};

// More entries...

// Load the GDT

struct gdt_ptr {

uint16_t limit;

uint32_t base;

} gdt_descriptor = {sizeof(gdt)-1, (uint32_t)gdt};

asm("lgdt %0" : : "m"(gdt_descriptor));

Who Can Read/Write GDT and LDT?

Reading:

GDT/LDT contents: Any code can read (they’re just memory) GDTR/LDTR values: SGDT/SLDT instructions (Ring 0 only)

Writing:

GDT/LDT contents: Only Ring 0 code should modify (by convention) GDTR/LDTR registers: Only Ring 0 via LGDT/LLDT

Memory Protection:

GDT location: Kernel typically places GDT in kernel-only memory pages LDT location: Can be in user-accessible memory (but user can’t change LDTR)

Post 80386 Era

- SGDT/SLDT: Ring 3 accessible (any privilege level)

- LGDT/LLDT: Still Ring 0 only

Why Intel Made This Change:

Practical Reasons:

- Debugging tools: Debuggers and system utilities needed to examine system state

- Virtual machines: VM software needed to read GDT/IDT information

- System monitoring: Performance tools and diagnostics required access

- Compatibility: Some software had legitimate needs to read (not write) this info

Security Analysis:

- Reading GDTR/IDTR: Reveals memory layout but doesn’t grant control

- Still protected: Only reading allowed - writing still requires Ring 0

- Limited exposure: Knowing GDT location doesn’t directly compromise security

Modern Usage:

This change enabled:

- Hypervisors: VMware, VirtualBox can inspect guest OS descriptor tables

- Security tools: Rootkit detectors can examine system structures

- Debuggers: WinDbg, GDB can show detailed system state

- OS utilities: System information tools can display memory management details

Task State Segment (TSS)

The Task State Segment (TSS) is a special data structure that contains the complete execution state of a task (program). Think of it as a “snapshot” that captures everything the CPU needs to know about a task - all its registers, memory settings, and execution context.

Before the 80286, task switching was a manual, error-prone process:

Manual Task Switching (8086 era):

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ 1. Programmer saves all registers manually │

│ MOV [task_a_ax], AX │

│ MOV [task_a_bx], BX │

│ MOV [task_a_cx], CX │

│ ... (save 20+ registers and flags) │

│ │

│ 2. Programmer loads new task's registers manually │

│ MOV AX, [task_b_ax] │

│ MOV BX, [task_b_bx] │

│ ... (load 20+ registers and flags) │

│ │

│ 3. Programmer manages memory segments manually │

│ MOV DS, [task_b_ds] │

│ MOV ES, [task_b_es] │

│ │

│ Problems: │

│ ❌ 50+ instructions per task switch │

│ ❌ Easy to forget registers │

│ ❌ No atomic operation │

│ ❌ No protection │

│ ❌ Very slow │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

TSS Solution:

Hardware Task Switching (80286):

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Single instruction: JMP task_selector │

│ │

│ Hardware automatically: │

│ ✅ Saves ALL current state to current TSS │

│ ✅ Loads ALL new state from target TSS │

│ ✅ Updates memory management (LDT switch) │

│ ✅ Atomic operation (cannot be interrupted) │

│ ✅ Hardware protection checks │

│ ✅ Extremely fast (few clock cycles) │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

TSS Structure and Layout

The 80286 TSS is a 44-byte (104 bytes with I/O bitmap 6) data structure containing every piece of information needed to resume a task:

TSS Layout (80286):

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Offset │ Size │ Field Name │ Description │

├────────┼──────┼───────────────────┼─────────────────────────┤

│ 00h │ 2 │ Previous TSS Link │ Selector of previous │

│ │ │ │ task (for nested calls) │

├────────┼──────┼───────────────────┼─────────────────────────┤

│ 02h │ 2 │ SP0 (Stack Ring 0)│ Stack pointer for Ring 0│

├────────┼──────┼───────────────────┼─────────────────────────┤

│ 04h │ 2 │ SS0 (Stack Ring 0)│ Stack segment for Ring 0│

├────────┼──────┼───────────────────┼─────────────────────────┤

│ 06h │ 2 │ SP1 (Stack Ring 1)│ Stack pointer for Ring 1│

├────────┼──────┼───────────────────┼─────────────────────────┤

│ 08h │ 2 │ SS1 (Stack Ring 1)│ Stack segment for Ring 1│

├────────┼──────┼───────────────────┼─────────────────────────┤

│ 0Ah │ 2 │ SP2 (Stack Ring 2)│ Stack pointer for Ring 2│

├────────┼──────┼───────────────────┼─────────────────────────┤

│ 0Ch │ 2 │ SS2 (Stack Ring 2)│ Stack segment for Ring 2│

├────────┼──────┼───────────────────┼─────────────────────────┤

│ 0Eh │ 2 │ IP │ Instruction Pointer │

├────────┼──────┼───────────────────┼─────────────────────────┤

│ 10h │ 2 │ FLAGS │ Processor flags │

├────────┼──────┼───────────────────┼─────────────────────────┤

│ 12h │ 2 │ AX │ General register AX │

├────────┼──────┼───────────────────┼─────────────────────────┤

│ 14h │ 2 │ CX │ General register CX │

├────────┼──────┼───────────────────┼─────────────────────────┤

│ 16h │ 2 │ DX │ General register DX │

├────────┼──────┼───────────────────┼─────────────────────────┤

│ 18h │ 2 │ BX │ General register BX │

├────────┼──────┼───────────────────┼─────────────────────────┤

│ 1Ah │ 2 │ SP │ Stack Pointer │

├────────┼──────┼───────────────────┼─────────────────────────┤

│ 1Ch │ 2 │ BP │ Base Pointer │

├────────┼──────┼───────────────────┼─────────────────────────┤

│ 1Eh │ 2 │ SI │ Source Index │

├────────┼──────┼───────────────────┼─────────────────────────┤

│ 20h │ 2 │ DI │ Destination Index │

├────────┼──────┼───────────────────┼─────────────────────────┤

│ 22h │ 2 │ ES │ Extra Segment │

├────────┼──────┼───────────────────┼─────────────────────────┤

│ 24h │ 2 │ CS │ Code Segment │

├────────┼──────┼───────────────────┼─────────────────────────┤

│ 26h │ 2 │ SS │ Stack Segment │

├────────┼──────┼───────────────────┼─────────────────────────┤

│ 28h │ 2 │ DS │ Data Segment │

├────────┼──────┼───────────────────┼─────────────────────────┤

│ 2Ah │ 2 │ LDT Selector │ Local Descriptor Table │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Memory Layout Visualization

TSS in Physical Memory:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Task A's TSS │

│ (44 bytes minimum) │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Offset 00h: Previous Task = 0x0000 │

│ Offset 02h: Ring 0 SP = 0x7C00 │

│ Offset 04h: Ring 0 SS = 0x0008 │

│ Offset 06h: Ring 1 SP = 0x0000 │

│ Offset 08h: Ring 1 SS = 0x0000 │

│ Offset 0Ah: Ring 2 SP = 0x0000 │

│ Offset 0Ch: Ring 2 SS = 0x0000 │

│ Offset 0Eh: IP = 0x1234 ← Where task will resume │

│ Offset 10h: FLAGS = 0x0202 │

│ Offset 12h: AX = 0x1234 │

│ Offset 14h: CX = 0x5678 │

│ Offset 16h: DX = 0x9ABC │

│ Offset 18h: BX = 0xDEF0 │

│ Offset 1Ah: SP = 0x7FF0 │

│ Offset 1Ch: BP = 0x7FE0 │

│ Offset 1Eh: SI = 0x1000 │

│ Offset 20h: DI = 0x2000 │

│ Offset 22h: ES = 0x0010 │

│ Offset 24h: CS = 0x0008 │

│ Offset 26h: SS = 0x0010 │

│ Offset 28h: DS = 0x0010 │

│ Offset 2Ah: LDT = 0x0028 ← Task's private memory │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

TSS Descriptor in the GDT

The TSS itself is just a data structure in memory. To use it, there must be a TSS descriptor in the GDT that points to it: (SInce TSS Descriptor is just another entry in GDT, it follows the same pattern as GDT entries)

GDT Entry for TSS:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ TSS Descriptor (8 bytes) │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Base Address: 0x00010000 ← Physical address of TSS │

│ Limit: 0x0067 ← TSS size (103 bytes) │

│ Access Byte: 0x89 ← TSS type, Ring 0 │

│ Flags: 0x00 ← Standard flags │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Access Byte Breakdown (0x89):

┌─┬─────┬─┬─┬─────┬─┬─┬─┐

│1│ 00 │0│1│ 001 │0│0│1│

└─┴─────┴─┴─┴─────┴─┴─┴─┘

│ │ │ │ │ │ │ │

│ │ │ │ │ │ │ └─ Accessed bit

│ │ │ │ │ │ └─── Reserved

│ │ │ │ │ └───── Busy bit (0=available, 1=busy)

│ │ │ │ └────────── TSS type (1001 = available TSS)

│ │ │ └─────────────── System descriptor (0)

│ │ └───────────────── Reserved

│ └────────────────────── Privilege level (00 = Ring 0)

└───────────────────────── Present (1 = valid)

Key Differences by Descriptor Type

Bits 3-0 Interpretation

Application Descriptors (S=1):

- Bit 3: Executable (1=code, 0=data)

- Bit 2: Direction/Conforming

- Bit 1: Read/Write permission

- Bit 0: Accessed by CPU

System Descriptors (S=0):

- Bits 3-0: System type (TSS, LDT, gates, etc.)

System Types:

0001 = Available 286 TSS

0010 = LDT

0011 = Busy 286 TSS

0100 = 286 Call Gate

0101 = Task Gate

0110 = 286 Interrupt Gate

0111 = 286 Trap Gate

1001 = Available 386 TSS

1011 = Busy 386 TSS

(others reserved)

Task Switching Process

When the CPU executes a task switch instruction, here’s exactly what happens:

Task Switch: JMP 0x0030 ; Jump to task with TSS at GDT entry 6

Hardware Sequence:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Step 1: Identify Target Task │

│ • Extract index from selector 0x0030 → Index 6 │

│ • Look up GDT entry 6 → TSS descriptor │

│ • Get TSS base address and verify it's a valid TSS │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Step 2: Save Current Task State │

│ • Get current TSS address (from TR register) │

│ • Save all CPU registers to current TSS: │

│ - Store AX at TSS+0x12h │

│ - Store CX at TSS+0x14h │

│ - Store DX at TSS+0x16h │

│ - ... (save all registers and flags) │

│ - Store IP at TSS+0x0Eh │

│ - Store segment registers │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Step 3: Mark Tasks │

│ • Set current TSS descriptor busy bit = 0 (available) │

│ • Set target TSS descriptor busy bit = 1 (busy) │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Step 4: Load New Task State │

│ • Load all registers from target TSS: │

│ - Load AX from TSS+0x12h │

│ - Load CX from TSS+0x14h │

│ - ... (load all registers and flags) │

│ - Load IP from TSS+0x0Eh │

│ - Load segment registers │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Step 5: Update Memory Management │

│ • Load LDT selector from TSS+0x2Ah │

│ • Update LDTR register → new task's private memory view │

│ • Flush segment register caches │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Step 6: Update Task Register │

│ • Store new TSS selector in TR register │

│ • Cache new TSS descriptor in hidden portion │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Step 7: Continue Execution │

│ • Begin executing at CS:IP from new TSS │

│ • Task switch complete! │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Total time: ~17-34 clock cycles (extremely fast!)

Privilege Level Stack Management

Each privilege level (Ring 0-3) needs its own separate stack for each program for security and proper operation:

Why Multiple Stacks are Needed?

Security Problem Without Separate Stacks:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ User Program (Ring 3) stack contains: │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ User data, local variables, function calls │ │

│ │ Potentially malicious or corrupted data │ │

│ └─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │

│ System Call (Ring 3 → Ring 0): │

│ If kernel uses same stack: │

│ ❌ Kernel data mixed with user data │

│ ❌ User could corrupt kernel stack │

│ ❌ Security vulnerability │

│ ❌ Kernel crash could corrupt user stack │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Solution - Separate Stacks:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Ring 0 Stack (Kernel): │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Kernel local variables, system call parameters │ │

│ │ Protected from user access │ │

│ └─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │

│ Ring 3 Stack (User): │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ User program data, function calls │ │

│ │ Cannot affect kernel operations │ │

│ └─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Stack Pointer (SP) and Stack Segment (SS) Explained

- Stack Pointer (SP): The offset within the stack segment where the stack currently “points”

- Stack Segment (SS): The selector that identifies which memory segment contains the stack

How Stack Switching Works?

Privilege Level Change Example:

User Program (Ring 3) makes system call:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Current State: │

│ SS = 0x0010 (user data segment) │

│ SP = 0x7FF0 (user stack pointer) │

│ CPL = 3 (Ring 3) │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

│

▼ INT 21h (system call)

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Hardware automatically: │

│ 1. Detects privilege change: Ring 3 → Ring 0 │

│ 2. Gets Ring 0 stack from current TSS: │

│ SS0 = 0x0008, SP0 = 0x7C00 │

│ 3. Switches to Ring 0 stack: │

│ SS = 0x0008, SP = 0x7C00 │

│ 4. Pushes Ring 3 context onto Ring 0 stack: │

│ - Push old SS (0x0010) │

│ - Push old SP (0x7FF0) │

│ - Push FLAGS │

│ - Push CS │

│ - Push IP │

│ 5. Loads interrupt handler address │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

│

▼

┌────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Now Running in Ring 0: │

│ SS = 0x0008 (kernel data segment) │

│ SP = 0x7BF6 (adjusted after pushes) │

│ CPL = 0 (Ring 0) │

│ │

│ Ring 0 stack now contains: │

│ [SP+12]: Old SS (0x0010) │

│ [SP+10]: Old SP (0x7FF0) │

│ [SP+8]: Old FLAGS │

│ [SP+6]: Old CS │

│ [SP+4]: Old IP │

│ [SP+2]: (space for kernel use) │

│ [SP+0]: (current stack top) │

└────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Ring 1 and Ring 2 Stacks

Ring Usage in Practice:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Ring 0: Operating System Kernel │

│ • SS0/SP0: Most critical system operations │

│ • Memory management, process switching │

│ • Hardware interrupt handlers │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Ring 1: Device Drivers (Rarely Used) │

│ • SS1/SP1: Device driver code │

│ • Some operating systems use this for drivers │

│ • Most modern systems use Ring 0 for drivers │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Ring 2: System Services (Rarely Used) │

│ • SS2/SP2: System service layer │

│ • Most systems jump directly from Ring 3 to Ring 0 │

│ • Some experimental OS designs used this │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Ring 3: User Applications │

│ • SS/SP: Normal application stack │

│ • Regular program execution │

│ • Cannot directly access lower rings │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Typical Stack Usage:

Most 80286 systems only used Ring 0 and Ring 3:

- SS0/SP0: Kernel stack

- SS1/SP1: Usually 0 (unused)

- SS2/SP2: Usually 0 (unused)

- SS/SP: User application stack

When user program makes system call:

- Hardware saves user context on kernel stack (SS0:SP0)

- Kernel operations use kernel stack space

- When returning, hardware restores user context

- User program continues with user stack (SS:SP)

Why Each Program Gets its own Kernel Stack Even though Kernel Code is Common for all?

If there was only one kernel stack for the entire OS, here’s what would happen:

Single Global Kernel Stack Problem:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Task A makes system call: │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Global Kernel Stack: │ │

│ │ [Task A's saved context] │ │

│ │ [Kernel local variables for Task A] │ │

│ │ [System call parameters] │ │

│ └─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │

│ Timer interrupt occurs → Task Switch to Task B: │

│ ❌ Task A's kernel context still on global stack! │

│ │

│ Task B makes system call: │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Global Kernel Stack (CORRUPTED): │ │

│ │ [Task A's saved context] ← Still there! │ |

│ │ [Task A's kernel variables] ← Still there! │ |

│ │ [Task B's saved context] ← New data overwrites! │ │

│ │ [Task B's kernel variables] │ │

│ └─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │

│ When Task A resumes: │

│ ❌ Its kernel context is corrupted │

│ ❌ System crash or data corruption │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Why Each Task Needs Its Own Kernel Stack

Each task gets its own kernel stack because:

- Task can be preempted while in kernel mode

- Kernel context must be preserved per task

- Multiple tasks can have pending system calls

- Recursion and nested operations

Shared Kernel Segment, Separate Stack Areas

The kernel memory segment is shared, but each task gets its own stack area within that segment:

Kernel Memory Layout:

┌────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Kernel Data Segment (Selector 0x0008) │

│ Base Address: 0x100000 │

├────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ 0x100000: Kernel Code │

│ 0x110000: Kernel Global Data │

│ 0x120000: Kernel Heap │

│ 0x130000: ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Task A Kernel Stack │ │

│ 0x131000: │ ← Task A's SS0:SP0 = 0x0008:0x31000 │ │

│ └─────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ 0x131000: ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Task B Kernel Stack │ │

│ 0x132000: │ ← Task B's SS0:SP0 = 0x0008:0x32000 │ │

│ └────────────────────────────────────────-────┘ │

│ 0x132000: ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Task C Kernel Stack │ │

│ 0x133000: │ ← Task C's SS0:SP0 = 0x0008:0x33000 │ │

│ └-────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ 0x140000: Other Kernel Data │

└────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Key Point: Same SS0 (0x0008), Different SP0 values

TSS Stack Pointer Management

Task Creation Process:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ When OS creates new task: │

│ │

│ 1. Allocate kernel stack space: │

│ kernel_stack_base = allocate_kernel_stack() │

│ // Returns something like 0x31000 │

│ │

│ 2. Set up TSS: │

│ task_tss.SS0 = KERNEL_DATA_SELECTOR // 0x0008 │

│ task_tss.SP0 = kernel_stack_base // 0x31000 │

│ │

│ 3. When task makes system call: │

│ Hardware automatically switches to SS0:SP0 │

│ Now using this task's private kernel stack area │

│ │

│ 4. When task switch occurs: │

│ Each task's kernel stack remains intact │

│ Next task uses its own SS0:SP0 values │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Real-World Example: System Call with Task Switch

Scenario: Task A calls file read, gets blocked, Task B runs

Step 1: Task A makes system call

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Task A (Ring 3): INT 21h ; Read file │

│ │

│ Hardware switches to Task A's kernel stack: │

│ SS = 0x0008, SP = 0x31000 (Task A's kernel stack) │

│ │

│ Task A's Kernel Stack (0x31000): │

│ [Task A's user SS:SP] │

│ [Task A's user FLAGS] │

│ [Task A's user CS:IP] │

│ [Kernel local variables for file operation] │

│ [File system state] │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Step 2: File not ready, Task A blocks

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Kernel: File not available, block Task A │

│ │

│ Kernel performs task switch to Task B: │

│ JMP task_b_selector │

│ │

│ Hardware saves current state to Task A's TSS: │

│ - Current SS (0x0008) → Task A TSS │

│ - Current SP (0x30F80) → Task A TSS ← Note: changed! │

│ - All registers → Task A TSS │

│ │

│ Hardware loads Task B's state: │

│ - SS = Task B's user SS │

│ - SP = Task B's user SP │

│ - SS0 = 0x0008, SP0 = 0x32000 ← Task B's kernel stack │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Step 3: Task B runs and makes system call

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Task B (Ring 3): INT 10h ; Video operation │

│ │

│ Hardware switches to Task B's kernel stack: │

│ SS = 0x0008, SP = 0x32000 (Task B's kernel stack) │

│ │

│ Memory State: │

│ Task A's Kernel Stack (0x31000): [Preserved file operation] │

│ Task B's Kernel Stack (0x32000): [New video operation] │

│ │

│ Both stacks coexist safely! │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Step 4: Task A resumes later

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ File becomes available, switch back to Task A: │

│ JMP task_a_selector │

│ │

│ Hardware loads Task A's state from TSS: │

│ - SS = 0x0008, SP = 0x30F80 ← Back to Task A kernel stack │

│ │

│ Task A's kernel stack is exactly as it was left: │

│ [Task A's user context] │

│ [File operation state] ← Still there! │

│ [Kernel variables] ← All preserved! │

│ │

│ Kernel completes file operation and returns to user │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Why This Design Is Necessary

Fundamental Requirements

- Reentrancy: Multiple tasks can be “inside” the kernel simultaneously

- Preemption: Tasks can be switched even while in kernel mode

- State Preservation: Each task’s kernel context must survive task switches

- Isolation: One task’s kernel operations can’t interfere with another’s

Alternative Approaches (Used in Some Systems)

Alternative 1: Non-preemptive Kernel

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ • Only one task in kernel at a time │

│ • Disable task switching during system calls │

│ • Simpler: can use single kernel stack │

│ • Problem: Poor responsiveness, no true multitasking │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Alternative 2: Kernel Threads (Modern Approach)

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ • Separate kernel thread handles each system call │

│ • User task blocks, kernel thread continues │

│ • More complex but better scalability │

│ • Used in modern operating systems │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

The Stack Collision Problem

How Stack Collision Occurs

Stack Growth Problem:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Normal State: │

│ 0x130000: ┌────────────────────────────────────────── ───┐ │

│ │ Task A Kernel Stack │ │

│ │ [Some data] │ │

│ │ [Some data] │ │

│ 0x130800: │ ← Current SP0 (stack grows down) │ │

│ │ [Free space] │ │

│ 0x131000: └─────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ 0x131000: ┌──────────────────────────────────────────── ─┐ │

│ │ Task B Kernel Stack │ │

│ 0x131800: │ ← Current SP0 │ │

│ │ [Free space] │ │

│ 0x132000: └─────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Stack Overflow Scenario:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Task A makes deep system call with many nested functions: │

│ 0x130000: ┌───────────────────────────────────────────── ┐ │

│ │ Task A Kernel Stack │ │

│ │ [Deep call stack] │ │

│ │ [Local variables] │ │

│ │ [More function calls] │ │

│ │ [Even more data] │ │

│ 0x130F00: │ ← SP0 approaching limit │ │

│ │ [Critical: Almost full!] │ │

│ 0x131000: └─────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ 0x131000: ┌─────────────────────────────────────────── ──┐ │

│ │ Task B Kernel Stack ← CORRUPTED! │ │

│ │ [Task A overflow data] ← Wrong task data! │ │

│ 0x131800: │ ← Task B's SP0 │ │

│ 0x132000: └─────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │

│ Result: Task A corrupts Task B's kernel stack │

│ System crash, data corruption, security breach │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Real-World Solutions

1. Stack Size Planning and Limits

Conservative Stack Allocation:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Better Layout with Larger Gaps: │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ 0x130000: ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Task A Kernel Stack (8KB) │ │

│ 0x132000: └─────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ 0x132000: ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Task B Kernel Stack (8KB) │ │

│ 0x134000: └─────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ 0x134000: ┌──────────────────────────────────────────-──┐ │

│ │ Task C Kernel Stack (8KB) │ │

│ 0x136000: └─────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │

│ Advantages: │

│ ✅ Larger stacks reduce overflow risk │

│ ✅ Clear boundaries │

│ ❌ Wastes memory if stacks are small │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

2. Guard Pages (Modern Approach)

Stack with Guard Pages:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ 0x130000: ┌───────────────────────────────────────--────┐ │

│ │ Task A Kernel Stack (4KB) │ │

│ 0x131000: └─────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ 0x131000: ┌────────────────────────────────────────--───┐ │

│ │ GUARD PAGE (unmapped/protected) │ │

│ 0x132000: └─────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ 0x132000: ┌───────────────────────────────────────-─────┐ │

│ │ Task B Kernel Stack (4KB) │ │

│ 0x133000: └─────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │

│ How it works: │

│ • Guard page has no memory mapped │

│ • Stack overflow triggers page fault │

│ • Kernel can detect and handle gracefully │

│ • Kill offending task instead of corrupting memory │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

3. Stack Bounds Checking

; Kernel stack overflow detection

check_stack_overflow:

mov ax, sp ; Get current stack pointer

cmp ax, stack_limit ; Compare with minimum allowed

jb stack_overflow_handler ; Jump if below limit

ret

stack_overflow_handler:

; Emergency handling:

; 1. Log the error

; 2. Kill the current task

; 3. Switch to a safe task

; 4. Prevent system crash

4. Dynamic Stack Expansion (Advanced)

Expandable Stacks:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Initial Allocation (Small): │

│ 0x130000: ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Task A Initial Stack (1KB) │ │

│ 0x130400: └─────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │ Expansion Area (monitored) │ │

│ 0x131000: ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Task B Initial Stack (1KB) │ │

│ 0x131400: └─────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │

│ On Near-Overflow: │

│ • Kernel detects stack approaching limit │

│ • Allocates more space if available │

│ • Updates stack boundaries │

│ • Continues operation │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

What 80286 Systems Actually Did

Typical 80286 Approach:

┌────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Conservative Fixed Allocation: │

│ │

│ 1. Large Fixed Stack Sizes: │

│ • Each task: 4KB-8KB kernel stack │

│ • Over-provision to avoid overflow │

│ • Waste memory but ensure safety │

│ │

│ 2. Task Limits: │

│ • Limit number of concurrent tasks │

│ • Reduce memory pressure │

│ • Simpler management │

│ │

│ 3. Programming Discipline: │

│ • Avoid deep recursion in kernel │

│ • Minimize local variables │

│ • Use heap for large data structures │

│ │

│ 4. System Monitoring: │

│ • Debug builds check stack usage │

│ • Runtime stack depth monitoring │

│ • Early warning systems │

└────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Example: OS/2 Approach

OS/2 Stack Management:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Thread Creation: │

│ • Default kernel stack: 8KB per thread │

│ • Configurable stack sizes │

│ • Stack committed on demand │

│ │

│ Stack Layout: │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Thread 1: 8KB kernel stack │ │

│ │ Thread 2: 8KB kernel stack │ │

│ │ Thread 3: 8KB kernel stack │ │

│ │ (Large gaps to prevent collision) │ │

│ └─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │

│ Protection: │

│ • Memory manager tracks allocations │

│ • Stack overflow detected by memory manager │

│ • Graceful task termination instead of corruption │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

How Modern Systems Handle This

Modern Approach (Linux/Windows):

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Virtual Memory + Guard Pages: │

│ │

│ Each process/thread gets: │

│ • Virtual address space │

│ • Guard pages at stack boundaries │

│ • Page fault handling for overflow │

│ • Dynamic expansion up to limits │

│ │

│ Benefits: │

│ ✅ No memory waste │

│ ✅ Automatic protection │

│ ✅ Scales to thousands of threads │

│ ✅ Hardware-assisted detection │

│ │

│ 80286 Limitations: │

│ ❌ No virtual memory/paging │

│ ❌ Limited memory management │

│ ❌ Must use simpler approaches │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Previous TSS Link

The Previous TSS Link supports task calling chains - when one task calls another task (not just jumps to it).

Task Calling vs Task Jumping:

Task Jump (JMP):

Task A ──JMP──→ Task B

│

└─ Task A stops, Task B runs

No way to return to Task A

Task Call (CALL):

Task A ──CALL──→ Task B ──IRET──→ Task A

│ │

└─ Task A suspended ──────┘

Task B can return to Task A

How Previous Task Link Works

Example Task Calling Chain:

Step 1: Main Program calls Print Service

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Main Program TSS (Selector 0x0030) │

│ Previous Link: 0x0000 (no caller) │

│ CALL 0x0038 ; Call Print Service Task │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

│

▼

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Print Service TSS (Selector 0x0038) │

│ Previous Link: 0x0030 ← Points back to Main Program │

│ CALL 0x0040 ; Call File I/O Task │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

│

▼

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ File I/O TSS (Selector 0x0040) │

│ Previous Link: 0x0038 ← Points back to Print Service │

│ IRET ; Return to previous task │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

When File I/O executes IRET:

1. CPU reads Previous Link (0x0038)

2. Switches back to Print Service TSS

3. Print Service continues where it left off

When Print Service executes IRET:

1. CPU reads Previous Link (0x0030)

2. Switches back to Main Program TSS

3. Main Program continues after the CALL

Hardware Behavior

CALL task_selector behavior:

1. Save current state to current TSS

2. Set target TSS Previous Link = current TSS selector

3. Switch to target task

4. Target task can later use IRET to return

JMP task_selector behavior:

1. Save current state to current TSS

2. Target TSS Previous Link unchanged (usually 0)

3. Switch to target task

4. No automatic return mechanism

TSS Benefits and Limitations

Advantages of Hardware Task Switching

1. Atomic Operation

- Complete task switch in single instruction

- Cannot be interrupted midway

- Guaranteed consistent state

2. Performance

- Extremely fast: ~17-34 clock cycles

- No manual register save/restore needed

- Hardware optimized

3. Reliability

- Cannot forget to save registers

- Hardware enforced privilege management

- Automatic stack switching

4. Security

- Memory isolation through LDT switching

- Privilege level enforcement

- Protected task linkage

Limitations and Problems

1. Memory Overhead

Each task requires:

- 44+ bytes for TSS

- 8 bytes for TSS descriptor in GDT

- Separate stacks for each privilege level

- Private LDT (optional but recommended)

For 100 tasks: ~5KB just for task management

2. GDT Size Limitations

GDT maximum size: 65536 bytes

Each TSS descriptor: 8 bytes

Maximum tasks: ~8000 (practical limit much lower)

3. Inflexibility

- Fixed TSS structure

- Cannot customize task switch behavior

- All-or-nothing: must save ALL registers

- Cannot optimize for specific use cases

4. Scalability Issues

Modern systems with thousands of threads:

- Would need thousands of TSS structures

- GDT would become enormous

- Memory fragmentation problems

Evolution Beyond 80286

Why Modern Systems Don’t Use Hardware Task Switching

Modern Software Task Switching:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Advantages: │

│ ✅ Flexible task structure │

│ ✅ Can save only necessary registers │

│ ✅ Custom scheduling algorithms │

│ ✅ Supports unlimited tasks │

│ ✅ More efficient memory usage │

│ ✅ Better cache performance │

│ │

│ Trade-offs: │

│ ❌ More complex kernel code │

│ ❌ Slightly slower (but caches help) │

│ ❌ Must be carefully implemented │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Legacy of TSS

Even though modern x86 systems don’t use hardware task switching for multitasking, the TSS remains important:

- One TSS per CPU for privilege level stack management

- System call stack switching still uses TSS stack pointers

- Interrupt handling relies on TS

The Memory Management Unit (MMU)

The 80286 was the first x86 processor to introduce an MMU (Memory Management Unit), but it was a simpler form than what we consider a “full” MMU today. The MMU in the 80286 is a hardware component integrated into the CPU chip itself. THe main purpose of MMU is to translate virtual addresses into physical addresses, along with checking bounds, enforcing privileges, etc.

Key MMU Functions Introduced by 80286

1. Hardware Address Translation

; 8086 - Software calculation:

; Physical = (DS × 16) + SI

; 80286 - Hardware MMU translation:

MOV DS, 0x0008 ; Load selector (points to descriptor)

MOV AL, [SI] ; MMU automatically:

; 1. Looks up descriptor for selector 0x0008

; 2. Checks permissions and bounds

; 3. Translates to physical address

2. Memory Protection

Descriptor Access Rights (enforced by MMU):

┌─┬─-─┬─┬─┬-─┬─-┬─┐

│P│DPL│S│E│DC│RW│A│ ← MMU checks these bits

└─┴─-─┴─┴─┴─-┴-─┴─┘

│ │ │ │ │ │ │

│ │ │ │ │ │ └─ Accessed (set by MMU)

│ │ │ │ │ └──── Read/Write permission

│ │ │ │ └─────── Direction/Conforming

│ │ │ └───────── Executable bit

│ │ └─────────── Descriptor type

│ └────────────── Privilege level (0-3)

└──────────────── Present bit

MMU generates protection fault if access violates these rules

3. Bounds Checking

Every memory access checked by MMU:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Descriptor Limit = 0x7FFF (32KB) │

│ Offset = 0x1234 │

│ MMU Check: 0x1234 ≤ 0x7FFF? ✓ Allow │

│ │

│ Offset = 0x9000 │

│ MMU Check: 0x9000 ≤ 0x7FFF? ✗ Fault │

└─────────────────────────────────────────┘

80286 MMU Components

1. Segment Register Cache (Hidden Descriptor Cache)

What Would Happen Without Segment Register Cache

Every Memory Access Without Cache:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Program executes: MOV AL, [DS:0x1234] │

│ │

│ Without caching, MMU would need to: │

│ 1. Read DS selector: 0x0010 │

│ 2. Extract index: 2 (from bits 15-3) │

│ 3. Calculate GDT address: GDT_base + (2 × 8) │

│ 4. Read 8 bytes from memory (descriptor) │ ← Memory access #1

│ 5. Extract base address from descriptor │

│ 6. Add offset: base + 0x1234 │

│ 7. Finally access target memory │ ← Memory access #2

│ │

│ Result: Every memory access requires TWO memory reads! │

│ Performance: 50% of memory bandwidth wasted on translation │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

How Each Segment Register Actually Works

Complete Segment Register Structure:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ DS Register │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Visible Part (16 bits) - What programmer sees: │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Selector: 0x0010 │ │

│ └─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Hidden Cache (64 bits) - Hardware only: │

│ ┌─────────────────┬─────────────┬─────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Base Address │ Limit │ Access Rights │ │

│ │ 0x00200000 │ 0xFFFF │ Ring 3, Read/Write │ │

│ │ (Physical addr) │ (Segment sz)│ (Permissions) │ │

│ └─────────────────┴─────────────┴─────────────────────────┘ │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Valid Bit: 1 (cache contains valid data) │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Instead of caching all GDT/LDT entries at MMU level, each segment register caches only one GDT/LDT entry - the one it currently points to:

Individual Segment Register Caches:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ CS Register: │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Visible: 0x0008 (selector) │ │

│ │ Hidden: [Base: 0x100000, Limit: 0xFFFF, Access: R/X] │ │

│ └─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ DS Register: │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Visible: 0x0010 (selector) │ │

│ │ Hidden: [Base: 0x200000, Limit: 0xFFFF, Access: R/W] │ │

│ └─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ ES Register: │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Visible: 0x0018 (selector) │ │

│ │ Hidden: [Base: 0x300000, Limit: 0x7FFF, Access: R/W] │ │

│ └─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ SS Register: │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Visible: 0x0020 (selector) │ │

│ │ Hidden: [Base: 0x400000, Limit: 0x1FFF, Access: R/W] │ │

│ └─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Each register caches ONE descriptor from GDT/LDT

Cache Loading Process

When Segment Register Is Loaded:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Program executes: MOV DS, AX (AX = 0x0010) │

│ │

│ Hardware automatically: │

│ 1. Store 0x0010 in DS visible part │

│ 2. Extract index: 2 │

│ 3. Calculate descriptor address: GDT_base + 16 │

│ 4. Read descriptor from memory (8 bytes) │

│ 5. Parse descriptor into components: │

│ - Base = 0x00200000 │

│ - Limit = 0xFFFF │

│ - Access = Ring 3, Read/Write │

│ 6. Store in DS hidden cache │

│ 7. Set valid bit = 1 │

│ │

│ This happens ONCE when segment register is loaded │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Fast Address Translation with Cache

Fast Memory Access Using Cache:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Program executes: MOV AL, [DS:0x1234] │

│ │

│ MMU hardware: │

│ 1. Check DS cache valid bit: 1 ✓ │

│ 2. Get base from DS cache: 0x00200000 │

│ 3. Get limit from DS cache: 0xFFFF │

│ 4. Check bounds: 0x1234 ≤ 0xFFFF ✓ │

│ 5. Calculate address: 0x00200000 + 0x1234 = 0x00201234 │

│ 6. Access memory at 0x00201234 │

│ │

│ Total: ONE memory access (the actual data) │

│ No GDT lookup needed! │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Cache Invalidation and Management

Cache Invalidation Scenarios:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ 1. Segment Register Reload: │

│ MOV DS, AX ; New selector → invalidate DS cache │

│ │

│ 2. Task Switch: │

│ JMP task_selector ; All caches invalidated │

│ │

│ 3. GDT/LDT Reload: │

│ LGDT [gdt_desc] ; All caches invalidated │

│ LLDT selector ; All LDT-based caches invalidated │

│ │

│ 4. Descriptor Modification: │

│ If OS modifies GDT/LDT in memory │

│ Must manually invalidate affected caches │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

What the 80286 MMU Provided

Segmentation-Based Memory Management The 80286’s MMU implemented:

- Address translation via descriptor tables (GDT/LDT)

- Memory protection with privilege levels (rings 0-3)

- Bounds checking to prevent segment overruns

- Access control (read/write/execute permissions)

What 80286 MMU Lacked

No Virtual Memory

- All segments had to exist in physical memory

- No demand paging or swapping to disk

- No virtual address spaces larger than physical memory

No Page-Level Protection

- Segment-level only - coarse-grained protection

- Cannot protect individual pages within segments